Beyond Neutrons: Why Gamma Noise Analysis Might Rewrite SMR Monitoring

Nuclear reactors require continuous monitoring to measure their power levels and ensure they don't drift toward unsafe conditions. For 60 years, we've done this by detecting neutrons—the particles that sustain the chain reaction—using sensors placed around the reactor core. The instrumentation community has spent decades perfecting this approach. We've built fission chambers that can survive 40 years inside pressure vessels, developed signal processing that can extract milliwatts of thermal power from noise, and written standards that dictate exactly where detectors must sit relative to the core.

This infrastructure works—mostly. But it was designed for reactors that don't exist yet.

Small Modular Reactors aren't just scaled-down PWRs. The NuScale Power Module, for instance, nests its core inside an integral pressure vessel, which sits inside a containment vessel submerged in a borated water pool. From a neutron detector's perspective, this is several meters of excellent shielding between you and the information you need. Water slows down (thermalizes) neutrons by scattering them until they're barely moving—precisely what you want for safety, but terrible for sensing. Traditional sensors, when placed outside this Russian-doll configuration, see a heavily blurred signal that has lost most of its valuable information.

Enter gamma rays—specifically, the prompt photons ejected within femtoseconds of each fission event.

Why Gamma Rays Work Where Neutrons Struggle

When a uranium-235 atom splits, it doesn't just emit 2.4 neutrons on average. It also sprays out roughly 7-8 prompt gamma rays per fission, along with delayed gammas from radioactive decay products and additional gammas when those neutrons eventually get absorbed elsewhere. This isn't just a physics curiosity—it's a statistical advantage that fundamentally changes what's possible in reactor monitoring.

Here's why: Reactor noise analysis works by detecting correlations between particles from the same fission chain. Think of it like listening for echoes to map a cave—you're not measuring individual sounds, but the patterns created when sounds from the same source arrive at slightly different times. The signal strength depends on how many particle pairs you can detect from each fission event. More particles per fission event means more coincident pairs, resulting in a stronger signal.

(For the statistically inclined: this scales with the second factorial moment of the particle distribution, written as $\langle \nu(\nu-1) \rangle$. Gamma's higher multiplicity gives it inherently better correlation statistics.)

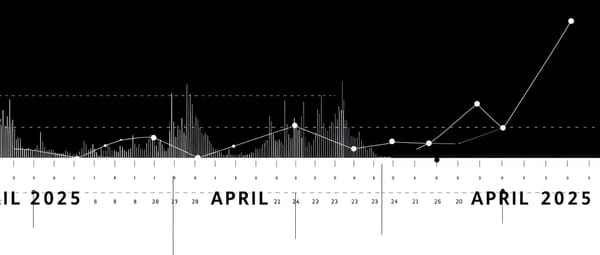

The CROCUS zero-power reactor at EPFL recently quantified this advantage in direct comparison tests. Using CeBr₃ scintillators for gamma detection versus standard U-235 fission chambers for neutron detection, they measured the same reactor parameter under identical conditions: the prompt neutron decay constant, which tells you how quickly the reactor would shut down if you removed the neutron source.

The gamma approach achieved a relative uncertainty of 1.3%event means more coincident pairs, resulting in.

The neutron approach: 3.6%.

That's not a marginal improvement—it's a factor-of-three reduction in uncertainty. In practical terms, this translates directly to faster anomaly detection during transients or tighter confidence intervals on reactivity measurements. During regular operation, you might not care whether your uncertainty is 1.3% or 3.6%. During an accident sequence or unexpected transient, that difference might determine whether your autonomous control system responds correctly within its design envelope or requires manual intervention.

The Seven-Meter Test

The more provocative result from CROCUS came from their stand-off measurements. They placed large Bismuth Germanate (BGO) detectors 7 meters from the reactor core, viewing it through the biological shield concrete, and successfully recorded mechanical noise signatures—fuel-assembly oscillations that modulate the fission rate at specific frequencies.

To put this in perspective: a thermal neutron detector placed seven meters from a reactor core, looking through typical shielding, would see essentially noise. It's like trying to hear a whisper through a concrete wall. The water and concrete scatter those slow-moving neutrons in random directions, destroying any coherent signal. But gamma rays at these energies (up to 8 MeV from fission) punch through—not unscathed, but with enough information intact to reconstruct what's happening inside.

This works because gamma rays and neutrons interact with matter in fundamentally different ways. Water moderates neutrons beautifully, scattering them until they've lost their directional information and most of their energy. But water is relatively transparent to multi-MeV photons, which are moving at the speed of light and don't "slow down" in the same way. Steel pressure vessel walls do attenuate gamma rays through processes called Compton scattering (bouncing off electrons) and photoelectric absorption (being absorbed entirely). Still, these interactions filter the energy spectrum rather than scrambling the temporal information—the timing relationships that encode vibration frequencies or reactivity oscillations.

The practical consequence: you can monitor an SMR from outside the pressure vessel, possibly even from outside the containment, using gamma detectors. This isn't about replacing in-core instrumentation—it's about enabling monitoring in configurations where traditional ex-core neutron flux measurement is either inaccessible or degraded beyond practical use.

Building a Gamma Detector That Works

The gamma noise concept stands or falls on scintillator performance, and here the materials physics creates interesting trade-offs. You need to match the detector type to the radiation environment.

For Stand-Off Monitoring (Outside Containment, Behind Shielding)

You need BGO (Bismuth Germanate, $Bi_4Ge_3O_{12}$). Its extreme density (7.13 g/cm³) and high atomic number mean a small BGO detector stops more high-energy gamma rays than a large plastic detector. When your gamma flux has already been attenuated by several meters of steel and concrete, you need every photon you can catch.

The trade-off is speed. BGO's scintillation decay time is around 300 nanoseconds—relatively slow in the detector world. At count rates above 150,000-200,000 counts per second, the detector can't recover between pulses fast enough. Pulses start overlapping (pile-up), which degrades your ability to measure correlations. But that's acceptable for stand-off applications where the shielding has already reduced the count rate to manageable levels.

For Near-Core Monitoring (Inside Containment, Close to the Vessel)

You need CeBr₃ (Cerium Bromide). With a decay time around 17-20 nanoseconds—more than an order of magnitude faster than BGO—it can handle count rates exceeding one million per second without saturating. This is essential when you're close to an operating reactor, and the gamma flux is intense. CeBr₃ also has the advantage of being intrinsically low-background, unlike some other scintillators (LaBr₃, for example) that have natural radioactivity built into their crystal structure.

The engineering challenge is keeping moisture out. Like most halide crystals, CeBr₃ is hygroscopic—it will literally dissolve if water gets to it. This requires hermetic encapsulation, typically a welded aluminum or stainless steel housing with no leaks whatsoever. That seal needs to survive decades inside a reactor containment environment (temperature swings, radiation damage, mechanical vibration). It's solvable, but it adds complexity to the passive safety qualification process.

For Large-Area Coverage (Safeguards or Portal Monitoring)

Plastic scintillators offer the fastest response time (around 2 nanoseconds) and can be manufactured cheaply in large sheets or panels. Some advanced plastics can even distinguish between neutron and gamma events using pulse shape discrimination—by analyzing how the light pulse rises and falls to identify the source. But their low density makes them inefficient gamma absorbers per unit volume. You'd need large slabs to compensate, which limits placement options inside compact SMR geometries.

The practical deployment likely involves a hybrid approach: CeBr₃ near the vessel, where flux is high and speed matters; BGO at stand-off distances, where efficiency per unit volume becomes the limiting factor; and possibly plastic panels for wide-area coverage, where physical footprint isn't constrained.

The Unexpected Safeguards Application

Beyond safety monitoring, gamma noise has a non-obvious application: verifying that reactor fuel hasn't been secretly replaced or tampered with—a concern for international nuclear watchdogs.

The International Atomic Energy Agency's challenge with SMRs—particularly those destined for export markets—centers on fuel diversion and proliferation resistance. Traditional safeguards rely on periodic inspections where IAEA staff physically verify fuel inventories. But what happens between inspections? How do you maintain "continuity of knowledge" that no fuel assembly has been swapped out with something different, or removed for reprocessing?

This is where the physics of gamma noise provides leverage. Plutonium-239 (which builds up in reactor fuel and is weapons-usable) has a different gamma multiplicity distribution and spectral signature than fresh uranium-235. As fuel burns, the changing isotopic mix leaves fingerprints in both the correlation strength and the energy spectrum of the gamma noise. In principle, a sealed SMR module could be continuously monitored for fuel replacement or unauthorized fuel cycle modifications without breaking containment—providing the continuity assurance the IAEA requires but struggles to maintain with portable instruments.

This hasn't been licensed yet. The technical demonstration exists (CROCUS and related research reactor experiments show it works in principle). Still, the regulatory pathway requires validation under full-power conditions and certification to safety instrumentation standards (IEC 61508 or equivalent). We're several years from deployment, but the concept has moved from theory to active development.

What's Not Solved Yet

The CROCUS experiments were conducted at zero power—essentially a critical reactor operating at a few watts rather than hundreds of megawatts. This is how you do physics experiments safely, but it means the reactor is "quiet": no boiling water, no accumulated fission products, no thermal noise masking your signal.

At full power in an actual SMR, you face a much messier environment. The delayed gamma flux from accumulated fission products (the radioactive debris from previous fissions) creates a huge background that can overwhelm the prompt signal you're trying to measure. These delayed gammas are uncorrelated—they're essentially random static—so they reduce your signal-to-noise ratio.

There are two approaches to dealing with this:

Energy discrimination: Set your detector to count only gammas above a specified energy threshold. Delayed gammas from fission products are typically lower energy (below 3 MeV), while prompt fission gammas go up to 8 MeV. By windowing your measurement to high-energy events only, you filter out most of the background. The downside is that you reduce your overall count rate, slowing your measurement statistics.

Frequency filtering: Look only at high-frequency components of the noise spectrum where delayed sources (with their seconds-to-minutes timescales) can't contribute. This works conceptually but requires extremely stable electronics and careful correction for dead time—the brief period after each pulse when your detector is blind to new events.

Both methods work in principle, but implementing them reliably over the long term requires ongoing validation testing.

There's also the question of long-term radiation damage. CeBr₃ and BGO are relatively radiation-hard compared to plastic scintillators, but multi-decade operation inside or near an SMR containment will accumulate neutron and gamma dose. The crystal structure could degrade, the light output could decrease, or the encapsulation could fail. The CROCUS measurements span hours to days, not the years or decades required for commercial reactor instrumentation. Accelerated-aging studies under combined neutron and gamma fields are in progress but are incomplete.

When This Might Actually Happen

If gamma noise analysis transitions from laboratory curiosity to deployed technology, it won't happen because it's "better" than neutron detection in some abstract sense. It will happen because specific SMR configurations—integral vessels, deep-pool submersion, and passive safety requirements that preclude active in-core electronics—create situations where neutron flux monitoring becomes impractical, and gamma detection offers a solution that meets the constraints.

The likely path forward involves dual systems: traditional neutron flux monitoring to satisfy existing regulatory requirements (the Nuclear Regulatory Commission doesn't move fast on instrumentation changes), supplemented by gamma noise analysis as a diagnostic or safeguards verification tool. As SMRs accumulate operating hours and performance data grow, standards might evolve to recognize gamma-based measurements as a primary safety indicator—but that's a decade away at minimum, possibly two.

Near-term deployment will probably happen first in research reactors and demonstration plants where regulatory flexibility exists. The first commercial application might be safeguards rather than safety, if IAEA requirements for continuous monitoring create a forcing function that drives development faster than traditional licensing pathways.

For now, this remains a specialist topic, confined to reactor physics laboratories and regulatory R&D programs. But the physics is sound, the hardware exists, and the boundary conditions imposed by SMR designs increasingly favor solutions that can see through steel.

The CROCUS benchmark data and detailed uncertainty analysis are available through EPFL's Laboratory for Reactor Physics and Systems Behaviour publications. Detector specifications are drawn from manufacturer datasheets (Saint-Gobain for BGO/CeBr₃, Eljen Technology for organics) and IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium proceedings.